(Football history.) Is it true that Everton is a Catholic club, and Liverpool is a Protestant club?

September 18, 2020

by Martin Odoni

Tradition has it that on Merseyside, there is a fundamental split between its two biggest football clubs on religious grounds. This split is presented as a kind of direct parallel of the Protestant/Catholic divide that causes so much heartache between Rangers and Celtic in Glasgow. This is understandable, as Liverpool is in some senses the ‘Glasgow of England’, in that it has a very substantial population of Irish descent, and that the city has had many sectarian troubles dating back to the nineteenth century.

The generally-accepted assumption is that Liverpool Football Club is Merseyside’s ‘Protestant club,’ and that Everton Football Club is Merseyside’s ‘Catholic club.’ However, this assumption has no particularly solid evidence to support it, and it appears based around the idea that, because football in Liverpool bears some points of strong resemblance to football in Glasgow, everything related to football in both cities must therefore be the same.

This is a silogistic fallacy; the football rivalry on Merseyside, while it may look very similar indeed to its Glasgow counterpart at first glance, is quite unique. The Merseyside Derby’s origin is a story of power struggles, a business feud that turned increasingly personal. And while religion did play a role, it was only a secondary feature. In particular, the origins of the two clubs on Merseyside are far more closely intertwined right from the outset than those of the ‘Old Firm’ giants, who came into being quite independently of each other.

A religious starting point

The history of the two big clubs on Merseyside does have a religious beginning, it must be said; namely, it starts with a chapel. In 1871, a quarter of a century before the district of Everton formally became part of the city of Liverpool, a new chapel was opened on the corner of Breckfield Road North and St. Domingo Vale. The chapel was named St. Domingo, after the local parish, and was ministered by the Reverend Ben Swift Chambers.

In 1877, Swift Chambers established a local cricket team, essentially to give boys and young men in the parish something to do to keep them out of mischief during the summer months. This proved quite a popular idea, but locals pointed out that it only worked during the cricket season. What do we do to keep the boys on the straight-and-narrow during the winter? they asked.

No problem. The following year, Swift Chambers also established a football team, which he called St. Domingo’s FC, to give the young men something positive to do during the darker months of the year. And it worked. Indeed, St. Domingo’s FC proved very popular, not just within the parish, but across Everton more widely, and even in neighbouring districts like Fazakerley and Walton. Not wishing to alienate or discourage this outside interest, the committee set up to run the football team chose, in November 1879, to adopt a new name; –

Everton Football Club.

It was all that simple really.

Religious, yes, but not Catholic

So far, so religious. How, you may be wondering, does this contradict the notion of Everton being a Catholic organisation? Well, this is how; Everton’s origins lie in the deeds of the man who ran St. Domingo’s chapel, and St. Domingo’s was not a Catholic chapel. It was neither built nor run by anyone connected to the Roman Catholic Church. Instead, it was a Methodist chapel. Indeed, the full name of the chapel was St. Domingo Methodist New Connexion Chapel. Methodism is essentially a nineteenth century, non-conformist spin-off of Protestantism, a new approach to Christianity arguing that the Church of England that emerged from the Reformation of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had taken a wrong turning at some point. Therefore, insofar as it had anything to do with the Protestant/Catholic divide at all, Everton would in fact lean towards being a Protestant organisation, not a Catholic one.

Furthermore, consider the site of Everton’s stadium, Goodison Park. There are two church buildings immediately on its doorstep.

One, St. Luke The Evangelist Church, is famously part of the stadium itself, in effect. It occupies the corner of Gwladys Street and Goodison Road; the stands at that corner had to be built around it, and this makes Everton FC seem almost intimately connected to Christianity. However, this again works against the idea of Everton being a Catholic organisation. Because St. Luke’s is an Anglican church, not a Catholic church.

Two, at the Stanley Park end of Goodison Road, immediately across the street from the famous Dixie Dean statue, is another chapel, called the Salop Chapel. You will not find any Catholic harbour here either; Salop is a Presbyterian chapel, and therefore more likely to have links to Rangers than to Celtic.

So when Everton famously departed Anfield in 1892, if the club board did so on pro-Catholic grounds, surely they would have chosen somewhere else to move to.

Liverpool FC – secular from birth

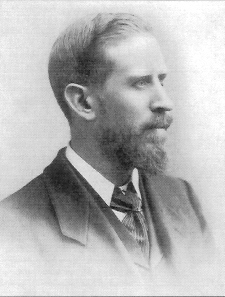

As for Liverpool, the club of course emerged as the result of an acrimonious split that developed within Everton Football Club. As I pointed out some years ago, there is a serious legal question mark over which club is really the older one, but most people accept the somewhat-misleading notion that John Houlding, the owner of Anfield, brought Liverpool into being in 1892 after Everton’s departure.

But as I indicate above, Everton did not depart Anfield on pro-Catholic grounds, and the schism between Protestants and Catholics had no detectable connection to the split of the club into two. The split instead centered around Houlding and disapproval of his ways of conducting business, and it developed into two angrily feuding factions whose differences became increasingly personal.

Houlding himself had arguably saved Everton from going to the wall, after the club found itself without a home ground in 1884. It had been playing home games on a field at Priory Road, just north of Stanley Park, for several years. But unfortunately, the ground was immediately next to the Anfield Cemetery. The noise of the crowds on matchdays was upsetting people who were visiting the graves of lost loved ones, and so the club was evicted. It was Houlding who found, and took out a £100-per-year lease on, a field on Anfield Road from the Orrell family, to keep Everton playing.

Unfortunately, the Orrells had not meant this to be a long-term arrangement. They were planning to redevelop the land for building on, starting in 1885, which would of course have made Everton homeless again after just a year.

The club committee went back to Houlding, asking him to find a solution. And so he did. After lengthy negotiations with John Orrell, Houlding persuaded him to sell Anfield to him, for £5,228, 11 shillings, 11 pence. (This is not very far short of half a million pounds in 2020 money.) Everton was saved a second time, but this time at a personal cost to Houlding. He had only managed to meet the purchase price by investing some £2,000 from his personal funds, and by borrowing £4,000 more; money, in short, that he could not really afford to spend. It was a massive financial risk he was taking, and for it to work out, he needed Everton to start becoming profitable, and for a substantial share of those profits to go into his own pockets, so he could start repaying the mortgage he had taken out on the land.

Until then, his reward would have to be adulation instead of opulence.

So by the end of 1885, Houlding was almost a hero figure among Evertonians, and had even been given the nickname, King John of Everton, as a tribute to his efforts to keep the club alive. He had already been made the club’s President and Chairman some time before, and although this was not as powerful a position as such titles might imply, it was still a testament to the high esteem in which he was held.

But as Houlding was to discover, nothing lasts forever, least of all fond sentiments when there is money involved.

Knives out for the King

It was after Houlding bought Anfield that relations between Chairman and committee started to sour. This purchase, Evertonians could be forgiven for assuming, should have meant the club was in clover, as its own Chairman now had control over the fledgling stadium and therefore had apparently secured its future. But Houlding’s conduct did not quite go as they perhaps imagined. Desperate to start recovering some of his outlay, once he had ownership of the ground, Houlding not only continued to charge the club rent, he went as far as to increase it, and would do so every year until 1892. By the 1889-90 season, the rent had increased to £250-per-year, a one hundred and fifty per cent increase on the original arrangement, and roughly five times the average rent paid by other clubs in the recently-established Football League. This was doubly aggravating to the club committee at Everton, given that when the Orrells had originally leased Anfield to Houlding in 1884, the £100-per-year rent had been set as a fixed rate.

None of this, of course, had anything much to do with religion, let alone the ‘Great Divide’ in Christianity. It really just boiled down to a dispute about money.

Anfield intemperance

Another issue that caused anger and resentment within the club towards Houlding contained the religious element of the split, but again, had little to do with Christian sectarianism. In fact, it was an argument about beer.

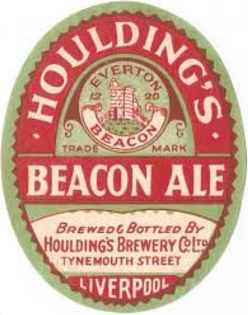

Houlding was, for better or worse, a business entrepreneur, and he had fingers in many a local pie, his main ones being building contracts, and, more pertinently, owning a local brewery. With Anfield now his own property, Houlding felt he had the right to use matchdays there to promote and sell the sparkling ales produced at his distillery on Tynemouth Street. He refused permission to anyone else to provide refreshments on the Anfield premises, thereby granting his brewery an effective monopoly.

This caused extra resentment for two reasons. Firstly, there seemed no necessity to have only one brand of refreshments available at the club, and it was surely an unfair hindrance to trade not to let anyone else provide or promote other labels at Anfield. But secondly – and this is the religious aspect – it must be reiterated that Everton was a Methodist club in origin. The great majority of its committee and membership were practicing Methodists, and one of the principles they adhered to with great resolve was what they called ‘temperance’ – the avoidance and discouragement of drinking intoxicating substances such as alcohol. Naturally enough, it offended most of Everton’s ‘tee-totallers’ (for want of a better name) to see their football club, set up to represent the Methodist community, actually selling alcoholic drinks during home matches! It was a little like a Rabbi pursuing a sideline in selling packets of bacon in the grounds of his own Synagogue. The ‘tee-totallers’ of the Everton committee therefore wanted Houlding to allow in other vendors to provide refreshments, especially ones who manufactured soft drinks.

Of course, one man’s model citizen is another man’s repressive killjoy, and Houlding, who was not a Methodist, or even a Christian by this time in his life, had little sympathy for anyone trying to impose religious moral absolutes on his paying customers; he continued selling beers regardless, and continued to keep Anfield out-of-bounds to other sellers.

There was a further issue over Anfield not having its own dressing rooms for players. On matchdays, the teams had to get changed into their playing colours in the rooms at the Sandon Hotel, which Houlding owned, just along Oakfield Road, and then walk to the stadium. Houlding put forward several proposals for building proper dressing rooms at the ground, but these were rejected by the club committee, who thought the set-ups suggested were unachievable. There were mutters from some committee members that Houlding had deliberately put forward unworkable proposals, because he secretly wanted players to keep using the Sandon, as it meant they were likelier to stop for drinks there after games, increasing his profits. Whatever the truth of that little conspiracy theory, it was unhelpful to the atmosphere at Everton that Houlding and the committee blamed each other for the lack of progress in supplying dressing rooms.

Relations between Houlding and many others at Everton were equally strained by political differences. Houlding was a Conservative. Many of the more prominent ‘tee-totallers’ were Liberals, and had grown to suspect the Chairman of using his pre-eminence at the club to advance his Westminster ambitions.

All-in-all, this particular Chairman-and-committee were the sort of combination that is usually doomed to fail.

Houlding’s grand plan, and the Orrells’ grand demand

Houlding had a complex plan, very rare among football clubs at the time, for Everton to be converted into a limited company. This would allow it far clearer and more firmly-defined restrictions on its liabilities within the law, while also allowing it greater financial and property rights than it held under its status purely as a sports club. Once a registered company, Everton could then simply buy Anfield from Houlding, and all arguments over rent would be settled then and there. Houlding would finally get his money back, allowing him to pay off the Anfield mortgage, and if the club committee wanted to let other vendors in on match-days to sell non-alcoholic refreshments, the decision would become theirs.

In fact, most of the club committee and wider membership agreed with the broad thrust of the proposal, but they were unhappy with the inner details of how Houlding planned for the company to be structured. It was very much to be a ‘top-down’ organisation, with the club Chairman, who would of course be John Houlding himself, given a lot of powers, and with a board of directors – the main check against such powers – set up as just a tiny handful of people. A different, more ‘democratic’ and more inclusive structure was proposed by other board members, and Houlding therefore had a fight on his hands if he was to get his way.

The matter of purchasing Anfield became critical early in 1892, when the Orrell family, who still owned land immediately adjacent to the stadium, invoked a clause in the 1885 rental agreement with Houlding. This could be activated in the event that development of the stadium led the Orrell remnant of land to be cut off from the main road. With new work done to expand the main stand in 1891, this is precisely what had happened; the club committee claimed that they had not been made aware of this clause before giving the go-ahead to begin the work. (Houlding would always insist that he had informed them, although no minutes of any official meetings at the club have been found to date that corroborate this.) The clause gave the Orrell family the right to force demolition of any part of the stadium that was obstructing access to their land via public thoroughfares.

The only reliable way Everton could prevent the demolition going ahead was therefore either to buy or rent the Orrell remnant of land, but Orrell and Houlding both insisted that that land could only be purchased at the same time as buying Anfield. Renting the Orrell remnant alone would cost an extra £120-per-year. Purchase of Anfield plus the Orrell remnant would require nearly £9,000 – roughly £740,000 in modern money – in an era when football clubs were tiny operations with little financial clout.

With Houlding still pushing for the club to convert to a limited company and buy Anfield, when the matter of this legal clause was finally raised, angry insinuations followed that he had deliberately set the whole scenario up to enrich himself and the Orrells. One particular remark about Houlding from an anonymous club member was so insulting that it was printed in the local news; –

“We could expect nothing but the policy of Shylock from Mr Houlding. He was determined to have his pound of flesh, or intimidate the club into accepting his scheme.“

Red Men: Liverpool Football Club The Biography, by John Williams, p.34.

Houlding responded to whispers of collusion by issuing the club committee with an eviction notice, establishing a clear countdown to the moment when the club must either buy up, or pack up; 30th April 1892.

This may have been a mistake on Houlding’s part, however. He had issued the notice to force the hand of the ‘tee-totaller’ faction, on the careless assumption that there was nowhere else available for Everton to play home games. With nowhere else to go, he reasoned, the only way to cancel the eviction would be to buy both Anfield and the neighbouring remnant of land.

However, the effective leader of the ‘tee-totallers,’ George Mahon, and his right hand man, Will Cuff, had been looking into the notion of moving the club away from Anfield altogether, and had discovered, on the opposite edge of Stanley Park, a suitable stretch of land off Goodison Road, called Mere Green Field. Mahon had successfully secured an agreement-in-principle to rent the land, and so when he proposed to the club committee that they move to new premises, and some heckler at the meeting called out, “You’ll never find one!” Mahon was able to retort, “I have one in my pocket!” producing, it was said, a not-yet-signed leasehold document with an elaborate flourish.

Which Everton is Everton?

Houlding made clear that if the move to Mere Green went ahead, he could not continue working with the club. But the committee voted by a wide majority in favour of Mahon’s plan, including converting to a limited company.

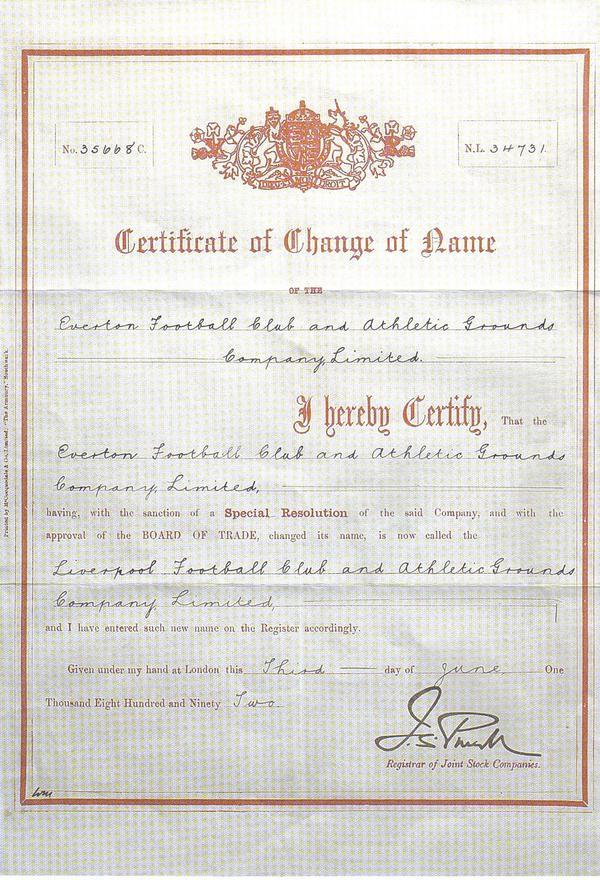

From there, Houlding and his allies, such as William Barclay and John McKenna, got together and attempted to secure the name of Everton Football Club for Anfield’s future. Now that the committee had approved conversion to a limited company, the only bar to such a conversion had been removed, and so Houlding et al decided to pre-empt this by themselves registering the club with Somerset House under the name Everton Football Club & Athletic Grounds Company Ltd. It was clear that Houlding was already planning simply to build a new team and continue football at Anfield, even if the incumbent staff there chose to leave. What was more, he wanted his new team to retain the name of the old one. If the old club left, it would have to find a new identity. Or so Houlding imagined.

On 26th of January, Everton Football Club was issued with company number 0035668, registered at the address of Anfield Road, with a certificate to this effect assigned to John Houlding.

The Everton club committee were absolutely furious when they discovered that the club had been converted into a company without their oversight, and worse, that Houlding held the certificate. This confirmed their increasingly vocal view of Houlding as a conman, a swindling cad who was exploiting the club for his own gain.

The committee responded by passing a Motion-of-No-Confidence in Houlding and his allies, who were thus all formally expelled from the club committee, and relieving Houlding of the Presidency once and for all. The club then started clearing out its every resource from Anfield, and moved the half-mile or so across Stanley Park to Mere Green Field. On this site, they began construction of a new stadium that would become known as Goodison Park, where they registered as a new company at that address, going by a similar-but-different official name; –

The Everton Football Club Company Ltd.

This new company had a registration number of 0036624. The split of Everton had become a reality, and there were now, in effect, two Everton Football Clubs – one on Anfield Road, one at Mere Green/Goodison Park.

The Football Association and the Football League, in a somewhat unusual moment between them of total agreement, intervened over the matter of which club was Everton and which was not. The FA ruled that they would side with whichever faction represented the majority of those who had been present in the original club. That meant that the Goodison Park faction was to retain the name and identity of Everton Football Club, as most of the committee, most of the membership, and most of the players, had made the move across Stanley Park. The Football League affirmed this decision by ruling that the Goodison Park club was to retain Everton’s position in the league.

Houlding gives up the fight for Everton

Houlding and his allies considered fighting this ruling, but appear to have decided that life was simply too short for a tug-of-war over a name. It may also have dawned on them that football was becoming less and less of a regionalised business by this time, and that their new club could benefit from having the pulling power of a more nationally-recognisable name than that of a moderately large suburb that was little-heard-of beyond the borders of Lancashire. Therefore, Houlding paid Everton a fee of £250 for the stands left behind at Anfield, as a final ‘divorce settlement,’ so to speak. Then, on 3rd June 1892, an amendment was approved to Anfield’s company certificate, and Everton Football Club & Athletic Grounds Company Ltd became; –

Liverpool Football Club & Athletic Grounds Company Ltd

If Houlding had hoped that the pay-off for the stands, and the handover of the club name, would lead to an amicable agreement between the two factions to differ and go their separate ways, he was to be sorely disappointed. Evertonians were still feeling intensely bitter towards him for, as they saw it, his attempt to steal ‘their’ club.

While some of Houlding’s practices had certainly proven rather dictatorial and ethically very shady, it is perhaps a shame that Evertonians took against him quite as completely as they had. Many of them seemed to have forgotten how, without Houlding’s expert business acumen, and his financial backing, Everton Football Club would probably have folded by 1887. That financial backing had, after all, been at Houlding’s own personal risk; he could easily have lost his near-£6,000 investment with no return, potentially ruining him, had the club not started making a profit subsequent to his purchase of Anfield. Gratitude in football, it seemed even in Victorian times, has an expiry date. (Ironically, the aforementioned Will Cuff, nearing the end of his life in the 1940’s, would receive similar harsh condemnation from Everton board members when he was accused, not very fairly, of trying to usurp the position of club chairman. A case of What goes around… perhaps?)

So relations across Stanley Park were to remain intensely bitter for years to come, with the two sides barely able to stomach talking to each other. Not a happy circumstance, given the proximity of the two stadiums was such that neither club could ever get out of the other’s sight.

Everton board members are even understood to have pressured other clubs into blocking Liverpool’s initial application to join the Football League in the summer of 1892. Liverpool had to play their first season in the Lancashire League instead, where they strolled to a regional championship, if not a national one. How instrumental Everton’s intervention was in getting Liverpool’s application rejected is a matter for speculation, but that they played some kind of role in it is incontrovertible. The nagging suspicion that George Mahon was the one pulling all the strings is in no way assuaged by the reason the Football League gave for rejecting Liverpool’s bid, which was certainly a bizarre one. The rejection letter stated that the club “did not comply to[sic] regulations.” What that meant was never made clear. Certainly it could not have been a problem with the stadium; Anfield had been hosting League matches only weeks earlier, before Everton had moved out.

With two other clubs having to resign from the Football League in the summer of 1893, due to financial and administrative problems, however, there was a sudden emergency-need to restore numbers. So Houlding re-applied for membership, and to Everton’s teeth-gnashing anger, this time the bid was successful; Liverpool were elected to the new Second Division (which had been established a year earlier as a result of the merger between the League and the short-lived ‘Football Alliance’ League). Ironically, this anger was precisely what made the decision to let Liverpool join very easy for officials at the League. By now, they had come to realise that the animosity between the two Merseyside clubs was so palpable that it had the potential to generate enormous public interest, should they have to play against each other at a national level.

Everton get increasingly spiteful

Everton would carry on trying to sabotage their ‘sibling-rivals’ for years to come, sometimes in ways that, on sober reflection, had no practical purpose behind them. For example, at the end of 1892, Everton refused to lend players to the traditional Christmas charity match, normally held at Anfield between two teams made up of top players from Merseyside’s four main professional clubs (the other two at the time being Bootle FC, and Liverpool Caledonian – both now defunct*). Everton insisted that, now their team no longer played at Anfield, the charity match should not be held there either, and should be switched to Goodison Park. Otherwise, Everton players would not take part at all. Liverpool came back with two alternative suggestions; one, the match could now be played at a neutral venue. Two, Goodison could host the match on this occasion, provided that the charity fixture was allowed to alternate between the two stadiums each year. Everton’s committee rejected both suggestions out-of-hand, without explaining what their problem was with either idea. The local press were scathing of the childish behaviour.

At the end of the 1892-93 season, the Merseyside Derby was finally born as Everton and Liverpool met on the field of play for the first time, in the final of the annual local competition, the ‘Liverpool Senior Cup,’ played at Bootle FC’s ground. Liverpool won a bruising and bad-tempered match 1-0. That was painful enough for Everton, but what made it intolerable was that the goalscorer was their former team-mate, Tom Wyllie, one of the very few players who had stayed at Anfield during the split. Worse, Everton were convinced they should have been awarded a penalty in the closing moments for an apparent handball. As soon as the final whistle blew, the Everton players and staff made a massive public scene, accusing Liverpool players of serious foul play, and the referee of doing a farcically bad job. (Sounds like a familiar Everton song.) The argument carried on for hours, with Everton forcing the organisers to carry out an immediate investigation into the staging of the match, and to check for possible corruption. Disappointed Liverpool players were denied the opportunity to receive the trophy while the inquest was carried out. At the end of it, Everton’s protest was dismissed – almost certainly correctly – as a frivolous case of sour grapes, and Liverpool received the trophy after all, but not on the day or in front of their supporters. (Again, familiar.) A rather cramped trophy presentation with a hemmed-in and very limited audience was carried out in the bar of the Sandon Hotel instead. Some of the casual support for Everton across the region appeared to transfer to Liverpool in the aftermath of the kerfuffle, as some of football’s less fanatical local observers expressed disgust at Everton’s lack of grace in defeat.

Given this backdrop, what happened next was doubly unfortunate. Liverpool lent out both the Liverpool Cup and the Lancashire League championship trophy, to be put on display in a furniture dealers’ shop window in the Paddington area of Edge Hill, a couple of miles south of Anfield. We will probably never know for sure who the criminals were, but several months after the ill-fated Senior Cup Final, thieves broke into the shop and stole both trophies. It was telling that the thieves did not appear to steal anything else – not even the two very ornate and rather valuable pedestals on which the trophies had been displayed. The only two objects that had been stolen were both football-related treasures. Liverpool had to pay over £120 to get the trophies replaced, and suspicious glances were swiftly directed towards Everton – towards fans more than the club, it must be stressed. The suspicion was that the theft was another act of spite to spoil the joy of Liverpool’s successful first season, and to sour the beginning of its first season in the Football League.

In February 1894, Liverpool hosted an FA Cup tie against Preston North End, who were the ‘glamour team’ of the time, and Anfield was expected to be packed with spectators for the match. Everton had been knocked out of the competition in the previous round, and so had an open Saturday that weekend. At very short notice, Everton arranged a completely unnecessary exhibition match against Sheffield United at Goodison Park, with kick-off at the same time as the cup tie. The Everton board were clearly hoping to put a huge dent in Liverpool’s projected gate receipts. This attempt did not, as it turned out, appear to have any effect. On the contrary, Anfield was so full on the day that a number of spectators had to be turned away, and many of them went to Goodison to cheer on Sheffield United at the exhibition match as their second choice. To add to Everton’s exasperation, Liverpool won the cup tie against Preston 3-2, to record the fledgling club’s most famous victory yet.

In the spring of 1904, Liverpool faced relegation from the First Division. Late in the season, the only other team that realistically might go down in their place, Stoke City, knew that a win at Everton might be enough for them to stay up. Everton were to finish just four points shy of winning the championship, and were comfortably tucked in third place in Division 1. The match with Stoke therefore should have been no contest, and yet Everton produced what was thought by observers to be one of their worst and laziest performances of the season. Stoke snatched a quite implausibly easy 1-0 win at Goodison Park, which eventually proved decisive in keeping themselves in the First Division, and in sending Liverpool down into Division 2. Supporters from the red half of Merseyside at the time were convinced that Everton deliberately threw the game just to make sure Liverpool were relegated, and arguments over that match have never completely gone away, even well over one hundred years later. No specific evidence that Everton actually rigged the game in some way has ever been uncovered, but the fact that they suddenly played so poorly at that precise moment was, even if not corrupt, perhaps still sufficient reason for Liverpool to feel aggrieved.

Some of this petty behaviour from Everton can be seen as quite amusing today, especially given how futile much of it proved to be. But this should not blind us to just how much genuine malice there was behind it, or just how seriously the mutual antagonism was felt by those who were there at the time. Anyone who cites the unrealistic and, frankly, rather patronising national media portrayal of Everton v Liverpool as ‘The Friendly Derby’ has probably not studied the history from any time prior to about 1950.

Meanwhile, Everton fans who frequently complain about their club getting the rough end of the stick against Liverpool may like to reflect that, when it comes to knowing how to behave vindictively, Everton is the club that wrote the book.

Spite, but no sectarianism

The fact that Liverpool is the club with the older company certificate – it still trades under company number 0035668 even today – is what raises questions over which of the two clubs is, under law, the original, but that is a matter I have discussed elsewhere.

The more pertinent detail is that, once more, there is absolutely nothing detectable in this remarkable saga that even touches upon the Protestant/Catholic divide at all. Liverpool was certainly not established as a ‘Protestant club’ at any stage in the split from Everton. Far from it; Anfield’s first board of directors after the split numbered six men, and of them, four were Freemasons i.e. not even Christians, let alone Protestants. That included both Houlding and McKenna – Freemasons, not Christians. Both men had links to the Orange Order, and both appear to have had a certain aversion to Catholicism – hardly surprising in McKenna’s case given he was a Unionist from Ulster – and that may be what gives the impression of Protestantism being a driving force at the club. But no, the club’s founding had little to do with religion at all, the religion of the majority of its board was not even a Christian denomination, and what religious priorities it had were mainly negative ones i.e. a wish to keep Methodists out so there were no more damaging rows over selling beer, and a politically-based desire to keep Catholics to a minimum, due to Unionist leanings and the tendency of Catholics to favour Irish independence.

These aversions do have something of a legacy at Anfield, mind you. Despite the huge Irish Catholic population on Merseyside, for instance, Liverpool never recruited an Irish Catholic to play for the team until Ronnie Whelan joined in 1979. But even there, there was no furore comparable to the notorious fan revolt in Glasgow when Maurice Johnston, a Catholic, signed for Rangers in 1989. Letting open Catholic worshippers play for Rangers may have been a reason to burn blue scarves in Govan and Ibrox, but when one of them joined the playing staff at Anfield, no one really cared about his religious preferences. Come to that, some years earlier, Tommy Smith, a local Catholic, not only joined Liverpool as a youngster, but also became one of the club’s longest-serving players. His religion was hardly ever an issue.

Everton, too, for a ‘Catholic club’, has shown little reluctance to sign Protestant players. Just for instance, the aforementioned Rangers sold Duncan Ferguson to Everton in the mid-1990’s, and he rapidly became a cult hero at Goodison Park, with not a hint of pushback from the fanbase.

There was a large Irish presence in the Everton team in the 1950s, and that might be where the Catholic associations stem from. There was also a popular Catholic doctor and Liberal politician in the city by the name of James Baxter, who in the late-nineteenth century joined the Everton board of directors. He is believed in some quarters to have drawn Catholics across the region in to start supporting Everton, although the numbers involved, even very approximate ones, have never accompanied the story.

A rivalry with no dividing line

The reality of the two fanbases, both in the city of Liverpool and beyond, is that there is no clear dividing line. Be it religious, social, historical, geographical, or even familial, there is no clear tendency influencing which of the two teams a football supporter on Merseyside is likely to support. Fans of both clubs are found in large numbers in all areas of the city, and always have been. Fans of both clubs are found with enormous frequency in the same family units, probably more so than in any other footballing rivalry, and, again, always have been. Yes, Catholics are about as likely to support Liverpool as Everton, and Protestants are about as likely to support Everton as Liverpool. Families of rich backgrounds, families of poor backgrounds, families of moderate backgrounds, if they are living on Merseyside, are as likely to have fans from both fanbases among their number as they are to have fans of only one of the two clubs.

The familial point is particularly strong, because in most parts of the world where there is more than one team, family preference is likely to be the decisive influence on which team a fan chooses, just as much as it will heavily influence which religion that person adopts. The fact that families on Merseyside tend to follow suit on religion, but can go either way on taste in football teams, is the most decisive bit of evidence available of the non-correlation between the two clubs and the Protestant/Catholic divide. Where fans do believe the myth of the teams being sectarian e.g. where a Protestant chooses to support Liverpool because of supposed Protestant sympathies at Anfield, they are probably doing so simply because of what they have heard, and not checked the history themselves.

It is a history they should feel is worth knowing. Partly because it is a remarkable and fascinating story in its own right. But more than that, without knowing such a history, without knowing what the rivalry is all about, what is the point of indulging in a rivalry at all?

* Liverpool Caledonian was a short-lived club set up in the Wavertree district to represent the sizeable Scottish expatriate community present on Merseyside in the 1890s. However, as Liverpool FC recruited most of its earliest players from north of the border – they were even given the nickname “The Team Of All The Macs” as a result – and that drew enormous interest from Liverpool-based Scots, the Caledonians quickly became superfluous, and closed down at the end of 1892.

The original Bootle FC, meanwhile, had a short but interesting story in the world of Merseyside football rivalries. The club was founded just one year after St. Domingo’s FC, and was one of the founding teams of the Football Alliance in 1889. It had been in the running to join the Football League in its founding year of 1888. However, to help spread the game across the country, only one club per catchment area was allowed initially, and Bootle missed out as Everton were awarded Merseyside’s only place. Bootle supporters were very unhappy about this, as Everton had been thrown out of the FA Cup five months earlier, due to improper payments to, and fielding of, seven ineligible players in a tie against Bolton Wanderers. From a Bootle perspective, this corruption – if corruption it was – should have been a decisive reason for Everton to be passed over by the League. Instead, Everton, then still playing at Anfield, were chosen chiefly due to the superior facilities (by the very basic standards of the time) at their stadium. So Bootle joined the Alliance instead, although this led to the club joining the Football League anyway in 1892, as a result of the merger of the two leagues.

However, Bootle was also one of the clubs – the other being Accrington FC – that had to resign from the Football League the following year, opening the way for Liverpool to join. Up until the emergence of Liverpool, Bootle had had very frosty relations with Everton for some ten years, and appeared likely to become their main rivals. Sadly, the club inevitably folded not long after withdrawing from the League.

A second Bootle FC was formed in the late-1940s and played in the old ‘Lancashire Combination’ League, but this incarnation of the club folded after about six years.

Yet another club called Bootle FC was established in the 1950s, although for its first twenty years it played under the name of Langton FC. It adopted the name of its predecessor club in 1973, and still plays today in the North-West Counties League. However, despite what is stated on its website, its claim to being descended from the club that played in the Football Alliance is dubious.

Tagged: Anfield, Anfield Road, Anglicanism, Ben Swift Chambers, Bootle FC, Catholicism, Celtic, Celtic Park, Dixie Dean, Everton, Everton Football Club, George Mahon, Goodison Park, Govan, Honest John, Ibrox Stadium, Joe Orrell, John Houlding, John McKenna, John Orrell, King John of Everton, Liverpool, Liverpool Football Club, Merseyside, Merseyside Derby, Merseyside football, Methodism, Old Firm, Parkhead, Protestantism, Rangers, St Domingos FC, Will Cuff, William Barclay

September 19, 2020 at 1:20 pm

Hi Martin thanks for this. Just a small corrective in terms of Rangers and Celtic. Rangers were formed a few years before Celtic and didn’t have a sectarian signing policy. That came later and ended (despite the delusions of some of their supporters) with the signing of Mo Johnstone. Celtic was formed at the institution of Father Walfrid with the intention of putting food on the table of the poor whilst providing sport and entertainment. The club was open to all, regardless of religion or beliefs and Celtic have had many protestant players and some supporters. Our most famous manager, Jock Stein, was a protestant who married a Catholic girl and had to leave Rangers as a result.

The division arose not at the origins of the clubs but with the development of the Irish independent movement and Unionism in Ireland and Scotland. Like several clubs (Hibs and Dundee United) Celtic was an Irish club in Scotland. Rangers became a Unionist club and adopted a sectarian signing policy.

The divide then isn’t a simple Catholic/Protestant one but this has been thrown in to explain the division. Even within Celtic there has been a divide between those who see the club as predominantly Scottish and those who who cherish the Irish origins of the club.

Celtic as a club has always been open to all, regardless of race or religion and to some degree politics. I became a Celtic supporter as a conscious socialist and whilst it’s not a necessity most socialists I met in Glasgow supported Celtic, not the club linked with the Tories, Rangers.

As for Liverpool Vs Everton most Celtic fans I have spoken to would tend towards Liverpool and not the BBC Everton Blues who seemed nearer to Rangers than Celtic. It’s a funny old world is football!!

September 20, 2020 at 1:32 pm

Well, I’m not sure that’s a ‘corrective’ as such, as I never really said anything to the contrary, especially nothing about Celtic having a ‘no-Protestants’ policy. I lived in Glasgow during my teenage years, and it’s quite impossible for a football fan living there not to learn the history of the Old Firm clubs, whether they want to or not. Indeed, when my family arrived in Glasgow in the summer of 1989, it was just as the Mo Johnston flare-up was getting under way. I was genuinely shocked and frightened watching it.

What I would say though is that Rangers and Celtic far more intimately embraced sectarianism than the Merseyside clubs ever did. Rangers in particular were quite flagrant in trying to stoke up anti-Catholic bigotry and anti-Irish-Independence feeling on many occasions, because they found the passions involved were good for their profits. The most blatant example I saw was the decision to introduce an orange away kit within a few weeks of the Good Friday Agreement being signed. It was one of the most shocking and manipulative acts of corporate cynicism I ever saw in my life, and I couldn’t picture either Everton or Liverpool doing anything comparable. It confirmed forever my utter contempt for Rangers Football Club.

Also though, there is no ‘other’ religion involved with the Old Firm. With Rangers, it’s a Protestant club or nothing. With Celtic, it’s a Catholic club, full stop (its founder was a Marist Catholic clergyman after all, trying to alleviate poverty mainly in east Glasgow’s Catholic community). Whereas on Merseyside, Everton is very definitely a Methodist club – the ‘Catholic’ tag is more less illusory. And Liverpool is a largely irreligious organisation, founded mainly by Freemasons. So the Protestant tag, also, is more or less illusory. It must be acknowledged that opposing sectarian groups frequently colonised the opposing fanbases on Merseyside during the 20th Century. But neither of the clubs ever really endorsed either denomination, and at times, both clubs were probably quietly wishing the Protestant-Unionist/Catholic-Republican groups would just go away. It wasn’t as if Liverpool and Everton didn’t already have enough to argue about!

I tend to have more sympathy for Celtic than Rangers, because it was always more on the defensive throughout the course of the rivalry. But at the same time, while acknowledging that Brother Walfrid’s intentions had been completely honourable, there is serious doubt about how much benefit the impoverished Irish communities in east Glasgow ever actually derived from Celtic’s existence, given the club quickly started seeking profits instead. (And, not that it’s relevant to the sectarianism issue, but the way the club betrayed Hibs and stole most of their players was pretty rank behaviour.)

September 24, 2020 at 12:43 pm

A fact that Hibs fans never seem to forget. Glad you seem to know a bit about the history. You seem to gloss over the sectarianism that did exist in Liverpool and may still do but the point I was making was that the original clubs weren’t sectarian at birth, regardless of later developments.

As to the charitable works of Brother Walfrid I guess it would have been difficult to spread the results of charitable work further than the area you were living and working in. Celtic’s charity arm dispenses it’s charity work in many parts of the world.

October 2, 2020 at 10:52 pm

I wouldn’t say I was glossing over the sectarianism in Liverpool. Indeed I mentioned it quite explicitly as a point of resemblance between the two cities. But as I say, it’s the clubs themselves I’m looking at more than the fanbases. And the Mersey clubs’ attitudes to it were less enthusiastic.

If the Old Firm and Merseyside derbies were really comparable, we would say Liverpool are the equivalent of Rangers. But where Rangers endorsed and even tried to magnify the sectarian issue, Liverpool seemed quietly embarrassed by it.

December 17, 2022 at 8:36 pm

I was exploring the protestant Catholic Everton Liverpool thing and was enjoying reading this until your assumptions spill over into speculation and feel biased. Shiny silver trophies stolen from a shop window must’ve been an orchestrated bitter blue conspiracy because they (couldn’t carry) didn’t take the bloody plinths. Do me a favour Columbo! Then there’s the first massively controversial derby, with a similarly bitter claim it was Everton led moaning rather than any corruption or conspiracy on Liverpool’s behalf. Without quality evidence, we’ll never know will we. Still, I read it to the end and who knows, maybe you’re right! Regardless, I’m confident that your fellow Liverpool supporters will enjoy the blue baiting bias you injected into your piece.

December 18, 2022 at 5:51 pm

I say to you what I say to a lot of people when they get over-defensive; STOP CHANGING THE MEANING OF WHAT YOU’RE ARGUING WITH. If you can’t argue with what is actually said, then you have no case.

Just to make clear, I did not say that Evertonians stole the trophies. I am not accusing anyone in particular, it’s quite possible that it was a random theft. What I said was that Everton troublemaking was the suspicion at the time. I described the timing of the theft as “unfortunate” precisely because, in the atmosphere between the two clubs that summer, it made that suspicion inevitable.

As for the Senior Cup Final, did you miss the bit where I mention that there was a full investigation carried out, and Everton could not present a shred of evidence to support their objections, beyond just they didn’t like the non-award of a penalty?

There was no blue-baiting bias in the article, but you appear to have been baited anyway. That says far more about the silly chip on Evertonian shoulders than it says about me.