Hillsborough, Heysel, Valley Parade and Ibrox: Why Are Stadium Disasters Always Prone To Urban Mythology?

December 9, 2013

by Martin Odoni

There were four great (if that is an appropriate word) tragedies that afflicted British football through the 1970’s and 1980’s – the second Ibrox Disaster of 1971, the Valley Parade Fire of 1985, the Heysel Stadium Disaster also of 1985, and the Hillsborough Disaster of 1989. Repercussions and reaction to them were varied in the extreme, from leaden-footed semi-interest from most of the country in response to Ibrox, to insensitive victim-blaming in response to Hillsborough. But one pattern that was completely consistent in their aftermaths was a false version of events becoming dominant in the wider public consciousness. All four disasters have a least one urban myth attached to them, sometimes minor, sometimes insidious, but they all have a note of false blame attached to one degree or another as well, and they all need dispelling.

With this in mind, there follows a description of one myth associated with each of the four tragedies, followed by an explanation of why that myth is untrue, and a description of what really happened in each case.

1st Myth – Ibrox. “Large numbers of fans were leaving the stadium, then suddenly turned and ran back towards the terraces in response to a late goal, colliding with other fans heading the other way.”

The notion that is still frequently perpetuated about the second Ibrox Disaster* in the New Year of 1971 (including, it saddens me to say, in the Report of the Hillsborough Independent Panel – see section 1.28 on page 30) is that the human crush that happened at the end of the game was a result of large numbers of Glasgow Rangers fans behaving in a reckless and somewhat fickle manner.

Most of the game, played between the two bitterest rivals in all of British sport, Rangers and Celtic, had been goalless and it appeared to be petering out into a tame draw. But entering the final minute, Bobby Lennox of Celtic struck a long range shot that hit the Rangers’ crossbar, and the ball looped out perfectly for Jimmy Johnstone to power a header into the net, for Celtic to take the lead. The myth assumes that thousands of Rangers fans, disappointed to see their team fall behind at the eleventh hour, started to head for the exits at this point. As the game headed into injury time however, Rangers got the ball down to the other end of the field, there was a scrappy scramble in the goalmouth, and Colin Stein forced the ball over the line for a similarly-surprising equaliser. The roar of celebration from the Rangers fans who were still on the terraces, the myth assumes, caused many of the fans who were on their way down the staircase that led out of the stadium to turn around and run back up the stairs to see what had happened. In doing this, it is imagined, they collided with a large body of other fans who had been following them, and this led many of them to fall down the stairs, and to land in a large pile at the foot of the staircase. In the crush that ensued, sixty-six people died, and over two hundred more were injured.

What actually happened; –

This famous myth is one of the earliest known examples of a British stadium disaster in which the victims get the blame for their own misfortune. The first aspect of it that is incorrect is the notion that the game was still being played when it happened. In reality, the game had already been over for at least several minutes – possibly as many as ten – by the time of the accident, which therefore could not have been a knock-on response to one of the goals being scored. The myth does not even make a great deal of sense. If the fans already descending the staircase leading out of the stadium – the notorious ‘Stairway 13’ – turned back in response to the roar of the crowd, why would the fans following behind them, who would have heard the roar even more clearly, carry on walking away?

In fact, eyewitness accounts all seem to agree that the flow of people at the time of the crush was all one way, and that was leading down the steps, away from the terraces. What appears to have happened was that one very young fan was sat on the shoulders of an adult who was descending the staircase. The adult lost balance, and the child fell forward off his shoulders, colliding with other fans ahead of them, causing them to stumble in turn and to collide with others ahead of them. This set in motion a kind of ‘domino effect’, as each person to stumble caused people in front of them to stumble, and people behind them to trip over them, and so on, until hundreds were tumbling down the steps.

The crush also did not happen at the foot of the staircase. Stairway 13 was divided into a number of flights, separated off by a series of short landings. The pile-up was on the landing at the top of the middle flight of steps.

What makes the mythological version of the Disaster’s cause insidious is that it implies that a large number of Rangers supporters were to blame for foolishly trying to push against the flow of the crowd on a staircase, and, in doing so, causing large numbers of people to fall, triggering a mass crush. This version, if accepted, would have spared authorities, especially Rangers Football Club itself, a considerable burden of responsibility for what happened. That responsibility is all-the-more significant when one considers the record of Stairway 13. This exit route from the stadium had had a worrisome history of safety issues dating back some ten years before the Disaster, all of which indicated that it was unsafe, owing to its steepness. Two people were killed and seventy were injured when falling on Stairway 13 in September 1961. Eleven more were taken to hospital after another mishap on the staircase in September 1967, and there were nearly thirty more injuries there in January 1969. After such a run of accidents, it should have become very apparent that something calamitous was going to happen sooner or later, but Rangers Football Club did little or nothing to modify or improve the staircase.

To try and say foolish crowd behaviour triggered the Disaster would therefore not just be inaccurate and unfair, it would also partly absolve Rangers Football Club of its culpability. In all fairness, the club did accept without any objections that the Disaster was the result of its own complacent failures, and to make sure that there could be no repeat, in the years that followed, Ibrox Park would be rebuilt from the ground upwards into a fully modernised all-seater stadium, setting by far the best safety standards of any football venue in the British Isles at the time.

Had the rest of the UK been paying proper attention to what happened, it might well have followed suit, but it was only really Rangers that was prepared to face the stark reality of how obsolete, dilapidated and inadequate British facilities for watching football had become. The general inertia everywhere else was probably partly because television pictures of the Disaster as it unfolded were non-existent, and so the full enormity of it was lost on most of the country. But it says something about the general ‘Yeah-but-that-was-Rangers-it-couldn’t-happen-here’ disinterest that it took fully sixteen months just for the Inquiry into the Disaster, conducted by Lord John Wheatley, to publish its findings. This lethargic attitude continued, both within football and within Government. After the Wheatley Report in May 1972, it took another year for the release of the first Green Guide laying out guidelines to improve stadium safety, and a further two years after that for Government legislation to follow, in the shape of the Safety At Sports Grounds Act. (And it took still another year for the renewal of the Green Guide to bring its recommendations into line with the Act. In all, it had taken five-and-a-half years after the Disaster just for the country to get to a starting position.) At no stage were the regulations stipulated in the Green Guide made mandatory, and implementation of them would be haphazard, grudging, and intermittent.

The legacy of the unheeded lessons of Ibrox would be more disasters, at Valley Parade and Hillsborough.

* The tragedy on Stairway 13 should not be confused with the first Ibrox Disaster. This occurred way back in 1902, when the same stadium was used to host the then-annual fixture between the national teams of Scotland and England. A temporary wooden stand, called ‘The West Tribune Stand’, had been set up above one of the terraces to allow extra spectators in to watch the game, but it had been weakened during the night before by torrential rain. Early in the second half of the game, part of the floor of the stand suddenly gave way, causing hundreds of spectators to fall over forty feet to the solid ground below. Twenty-five people were killed, and over five hundred others were injured.

2nd Myth – Valley Parade. “Some idiot at Bradford City locked the exit doors at the back of the main stand, and no one could get out when the fire broke out.”

This myth is not exactly insidious, but it is somewhat unfair.

The Valley Parade Fire of 11th May 1985 was perhaps the most horrifying of the four stadium disasters because of the unrelenting speed at which events unfolded.

The 1985 fire at Valley Parade is famous for taking just four minutes to fill the main stand from end-to-end. But, while this is technically true, it is even more shocking to realise how quickly it spread from filling one section of seating to filling out the stand in its entirety – not much more than *one* minute.

The fire took fifty-six lives and left terrible scars on many of its survivors, and there is no doubt that abysmally poor safety standards were once again at the heart of what went wrong. But there is a common misunderstanding about one aspect of that.

The myth goes that the deaths were caused because most of the fans in the main stand ran to the exits in the back wall, only to find when they got there that they were all locked. While this is accurate in a manner of speaking, the emphasis is misleading as it implies that Bradford City Football Club had a myopic policy of preventing safe evacuation routes, purely for the sake of keeping non-ticket-holders from sneaking into the stadium. This impression still seems commonplace among the football public.

What actually happened; –

In fact, while it is technically true that the doors were locked, it was only in a way that, in most circumstances, would not have presented a serious obstacle at all. What is not usually mentioned or understood when discussing the matter is that the doors at the back of the stand were all standard Fire Exits, of a typical Push-bar-to-open-door variety. The doors all had the familiar horizontal release bars at roughly waist height, which when pushed would have allowed easy escape.

The real problem was not the locks, it was that these were not ‘most circumstances’. Due to the highly combustible materials that the aged timber stand was made from, and the dizzying speed at which the fire was spreading, the air was absolutely saturated with an immensely thick miasma of black smoke. After just a few moments, any people still in the stand were almost completely blinded, and they all effectively had to orient themselves by touch alone – by feeling their way around the seating and along the back wall, to find a route to the narrow passageways that led to the exits. By the time anyone finally reached an exit, they would be so confused by the lack of vision and by smoke-inhalation that finding the release bars in order to push them was a difficult task in itself, and the fire was approaching so quickly that they did not have long in which to find them. The problem was complicated further by the release bars having elaborate ‘plastic-loop’ locks on them, that were almost impossible to operate when effectively blindfolded.

Many spectators failed.

Another aspect in the myth that is misleading is the implication that hardly anybody escaped the fire. While fifty-six is a horrific death-toll, it is far from true that it amounted to the majority of spectators who had been there that day. It was, after all, a promotion party, as Bradford City had just won the then-Third Division Championship, and so there was a much higher than usual attendance that day. There had in fact been approximately three thousand spectators in the main stand at the time the fire broke out, and the great majority of them escaped uninjured. This was because most of them evacuated by climbing over the advertising boards around the perimeter onto the field of play, instead of heading for the back of the stand.

There were many aspects of poor safety at the Valley Parade Stadium that Bradford City deserved criticism for. The stand, which by a sad irony was due to be part-demolished just two days later to be replaced with a state-of-the-art modern-roofed grandstand, was clearly far too old and badly maintained. There were no fire extinguishers available, which seems shocking enough in any place of communal entertainment, let alone one that was made largely of wood. Large amounts of combustible litter had been allowed to build up under the stand dating back at least thirty years, which played a critical role in the fire breaking out in the first place – and yes, the club had been warned about it several times beforehand that it posed a serious danger. The turnstiles had been locked, which prevented one possible evacuation route – indeed some victims died not of burns or inhalation but of crush injuries from making an unsuccessful attempt to escape by crawling under the turnstiles.

Yes, safety standards at Valley Parade were appallingly low, but the locked exits myth is not really true. We also must keep in mind the poverty of Bradford City at the time – the club had actually folded a couple of years earlier and was only resurrected when a former board member, Stafford Heginbotham, was able to buy up the assets and to cover the wage-bill to keep fielding a team. And in all fairness to Heginbotham, at the time of the Disaster, as the club’s new chairman he had only just started a gradual process of reforming the ground, when he had scant resources with which to do it. At the very least, he was the first chairman the club had had in a long time who was prepared to face the reality of the need for reform. The horrendous condition of Valley Parade was a situation he had very much inherited, not one he had created.

(For more insights into this subject, I highly recommend reading Four Minutes To Hell: The Story Of The Bradford City Fire, written by Paul Firth, one of the survivors. Unsurprisingly, it is often a very harrowing read, but very diligently and articulately written. There are also more details analysing the Bradford Fire on this blog, which can be read here and here.)

3rd Myth – Heysel. “Scousers were the worst hooligans in the 80’s. At Heysel, they were murderers who pushed a wall onto Juventus fans!”

The Heysel Stadium Disaster happened less than three weeks after the Valley Parade Fire, and it is fair to suggest that, had it not happened, the Fire would be far more vividly remembered today.

The Disaster in Brussels was probably the most notorious episode of hooliganism in the history of European football, chiefly because the chaos was broadcast live on television all around the world – it happened shortly before the 1985 European Champions’ Cup Final was due to kick off.

Now, this is certainly no attempt to exonerate or defend the behaviour of the supporters of either team in Brussels on the night of the Disaster, but it is beyond doubt that the Heysel Disaster is, both in terms of identifying the events on the day and of identifying its causes and origins, a leading candidate for being the single most widely misunderstood and most wildly mythologised football disaster of all.

The mythological version has it that supporters of Liverpool Football Club, with a supposed history of routinely violent behaviour at the time, travelled to Brussels for the European Cup Final against Juventus of Italy in the mood for a fight. When they got into the stadium, so the myth has it, they sought out the nearest enclosure to contain a large presence of Italian supporters, then stampeded into it and started murdering them indiscriminately, before pushing over a wall onto their opponents.

This portrayal of events sounds far too vivid and crude to be true even without analysing the facts first. And sure enough it is too vivid and crude to be true.

What actually happened; –

The real causes of the Heysel Disaster were far, far more complex and varied than a simplistic, stereotyped “Scousers-were-looking-for-trouble” narrative, and the loss of life on the night, while inexcusable, was certainly not murder. And although the immediate responsibility for the Disaster does, in the end, lie with the Liverpool supporters, the blame is far from exclusively theirs. What really happened, and why it happened, is quite a long and complicated story, as shall be outlined below.

It is also utterly untrue to claim that Liverpool fans had a particularly bad reputation or record of misbehaviour at the time. It was not exactly free of blemishes, no – many Liverpool fans had a deserved reputation for kleptomania when on their travels around the continent – but given that the club had played far more European matches than any other British side by that point, the history of Liverpool supporter-conduct abroad was remarkably good. Certainly it was far better proportionally than the usual behaviour of fans of the England national team at the time, or of clubs such as Tottenham Hotspur or Leeds United. (Those who blame Liverpool for the five-year ban imposed on English clubs from taking part in European competition after 1985 are looking for scapegoats for a problem that, in reality, was almost endemic across the country.)

Equally, the story of Liverpool fans pushing over a wall onto the Juventus fans appears to be a long-running ‘Chinese whisper’. A wall did fall over in the Heysel Stadium during the Disaster, but it was not deliberately pushed over by anybody.

The root causes of the Disaster itself were actually sowed in previous years. In 1982, the European football union, UEFA, was looking for venues to host the European Cup Final over the next few years, and was invited to consider Heysel. The stadium had hosted the Final three times previously, including in 1958, only the third European Cup Final ever played. It had also hosted three Finals of the European Cup-Winners’ Cup, one of the secondary European competitions (now defunct).

What UEFA does not appear to have been made aware of, or perhaps just did not put much thought to, was that the Heysel Stadium was in fact in an advancing state of disrepair. It was already over fifty years old and the very concrete it was constructed from was decaying. Arsenal supporters had attended a Cup-Winners’ Cup Final there in 1980, and they had concluded unanimously and unreservedly that it was ‘a dump’. Indeed, a demolition order had been served on the stadium, which was expected to be carried out in 1986. With this order in place, the authorities in Belgium did not bother to continue with maintenance work on the ground, the attitude being “Why waste money repairing something when we’re going to demolish it soon anyway?”

Whether UEFA ever bothered to carry out a formal inspection of Heysel before making its decision is not completely clear. The rumour, perhaps an apocryphal story, is that a UEFA delegation did attend the ground in the winter of 1982-83, but that it was so cold on the morning of the inspection that they decided to give it a miss, and just approved the stadium. “It’s hosted European Finals before,” seemed to have been the thinking, “it can host one more.” This sounds so casual, especially given the demolition order that was already in place, that the story needs to be treated with caution. But it has to be said, it does seem to have an uncomfortable ring of truth to it, if only because, had an inspection in fact gone ahead, it seems inconceivable that the UEFA delegates would have agreed to let the biggest sporting fixture in all of Europe be played there.

Whatever the reality of that, the reality of the stadium was that it was not in a condition fit for a crowd at a Third Division League match, let alone a European Cup Final. The perimeter walls, made of aged cinder-block, were brittle and worn. The concrete surface of the terraces had long-since broken up into loose blocks resting on top of the foundations. Fences were feeble and rusted. The ground would have been hard-pressed to host a meeting of a local Rotary Club in adequate safety. But it was eventually confirmed to be the venue for the 1985 European Champions’ Cup Final.

In May 1984, Liverpool Football Club reached the Final. It was the club’s fourth appearance in the Final since 1977, and on all three previous appearances, the team had gone on to lift the most prestigious trophy in European sport.

This year, their opponents would be an Italian club, AS Roma, who were a major force in Italian football at the time, but had still never become European Champions. This was surely Roma’s best-ever opportunity to do so however, for the venue chosen for the European Champions’ Cup Final was the Stadio Olimpico… in Rome. Yes, UEFA had allowed Roma’s home stadium to be the venue for a European Cup Final that Roma’s own team was to appear in. Although Liverpool was the team with by far the greater European pedigree, with home advantage it was Roma who went into the Final as the clear favourites to win.

But Liverpool won. After two hours of football had failed to separate the two teams, Liverpool’s nerve held better in the penalty shoot-out that followed, and they lifted the European Champions’ Cup for the fourth time.

Among the seventy thousand spectators in the Stadio Olimpico, there were approximately five thousand Liverpool supporters. When the shoot-out ended, they should have been in a state of joyous delirium. Instead, those who were there still recall being gripped by a sensation of real terror. The atmosphere around the rest of the stadium turned very, very ugly in just seconds as the Roma fans began to recognise the taste of bitter defeat. Knowing they were outnumbered by roughly thirteen-to-one, and noticing the waves of hostility emanating from their beaten rivals, many of the Liverpool supporters began to worry whether they would be able to escape the Eternal City with their lives.

They had good reason to worry.

Immediately upon getting out of the stadium, hundreds of Roma fans, most of them ‘Ultras’ (extreme fanatics) returned to where they had parked their cars, and from within, they retrieved weapons that had been concealed inside, including machetes. They then waited at the exit allocated to the Liverpool supporters, whom the police had kept from leaving the ground until after all the Italian fans were gone.

Almost as soon as the Liverpool supporters were allowed out of the stadium, the armed Ultras were upon them, hurling missiles at them, and slashing at them with knives. If the Liverpool supporters expected the police to help and protect them, they were to be sorely disappointed. Any appeal for help was met with police violence against the Liverpudlians, who found themselves being kicked and punched by officers who seemed to believe that the nationality of a football fan was all that mattered when establishing who was an aggressor.

For hours through the night that followed, terrified Liverpool fans tried to find a safe path through the city back to their hotels, repeatedly having to take refuge from blade-wielding, bloodthirsty motorcycle gangs, who were patrolling the streets to find Englishmen to take revenge upon on behalf of their team.

Many fans did make it to their hotels more or less unscathed, but for some of them, the nightmare did not end there. For some of the hotel owners suddenly refused them access to their rooms, fearing that to allow them in would make their hotels targets for further attacks. In the end, many of the Liverpool supporters had to go as far as to take refuge in the British Embassy.

No one had actually been killed during the ‘Night Of The Roman Knives’, but it was not for want of trying. Dozens were injured, and many were hospitalised.

The whole chapter of violence was met with expressions of outrage and shame in the Italian media the next day, but to the shock and anger of many Liverpudlians, there seemed to be an almost total blackout of coverage in the British press. The Conservative Government of Margaret Thatcher, probably for political reasons, was stonily silent about it, failing even to go through the formality of registering an official complaint with the Italian Government – perhaps for fear of evoking sympathy for socialist Liverpool.

The upshot of this violent episode was two-fold;-

Firstly, people from Merseyside became increasingly convinced that they could not count on their own Government to protect them or to speak up for them when they were the victims of wrongdoing when abroad, and that in the event of future confrontations, they were going to have to look out for themselves, by any means necessary.

And secondly, those who had witnessed or become embroiled in the attacks swiftly developed a deeply-felt, generalised fear and resentment of Italian football fans. It was not a well-informed fear, nor was it a fear that would justify counter-violence, but it was entirely comprehensible.

So can anyone fail to imagine the reaction of at least some of the Liverpool fanbase a year later when, on qualifying for the Final again, they learned that their opponents at Heysel would be another Italian club – Juventus of Turin?

In the weeks leading up to the 1985 Final, UEFA made another bewildering decision, this time regarding ticketing arrangements. The seating areas in the stands would be allocated to neutrals and dignitaries, while the supporters of Liverpool and Juventus were allocated opposite ends of the stadium, sensibly enough. Each end of the Heysel Stadium had a semi-circular terrace, divided by wire fencing into three sections or ‘blocks’. All three blocks at the Juventus end of the stadium were awarded to the travelling Italian support. But the Liverpool contingent was (wrongly) expected to be much smaller, so they were only given two blocks at their end. It was decided that the third block, known as ‘Section Z’, should be used as another ‘neutral’ space for casual spectators. And tickets for this space were made freely available on the local market.

This was, to put it as politely as possible, an unwise decision.

In fact, to blazes with politeness, it was downright idiotic.

The problem was that the fixture was being held in Brussels, which had an enormous Italian expatriate community. Juventus was the most popular football team in Italy (and still is), so naturally enough, many of the expatriate Italians living in Brussels were Juventus supporters. So when tickets to a European Cup Final, featuring Juventus and to be played in Brussels, went on open sale on the Belgian market, guess whose hands most of them ended up in?

(Clue: Not Liverpool fans.)

(Another clue: Not neutrals either.)

The situation therefore was that on the terrace allocated to the fifteen thousand Liverpool supporters, one section with a capacity of over five thousand was going to be occupied in the main by Juventus supporters. And the two contingents were only going to be separated from each other by a thin length of chain-link fencing (‘chicken-wire’). Just a couple of yards from each other, and with many of the Liverpool supporters still haunted by memories of the dreadful treatment they had received in Rome a year earlier.

Hardly surprisingly, both Liverpool and Juventus protested to UEFA in the weeks before the Final that the arrangements were an invitation for trouble. But as was so often the case with UEFA when it faced objections to its policies, it just tried to deal with the difficulties highlighted by sneering at them.

A few days before the Final, Liverpool Football Club lodged another protest. Representatives of the club had finally been given a chance to survey the Heysel Stadium, and they were absolutely appalled by what they saw. The stadium was literally crumbling. The terraces at either end of the ground were just collections of cracks loosely-connected by stretches of decaying concrete. Walls looked barely capable of keeping out a light breeze. The stadium was entirely unsuited to its task. One or two officials at Liverpool seriously considered refusing to play the Final. But again, UEFA did not listen. Knowing that withdrawing from the Final would lead to repercussions, and probably considerable public criticism, Liverpool backed down, but with an ongoing air of trepidation.

For much of the day of the match, there seemed to be plenty of signs that the worries of the two clubs were unfounded. English and Italian supporters mingled freely and happily around the streets of Brussels, and the atmosphere was mainly celebratory. Much alcohol was consumed, but that only seemed to heighten the cheer. It was only as the sunny afternoon gave way to a humid evening that the mood began to darken. As more and more fans of both sides neared the stadium, suspicion began to replace friendliness. Rumours of minor clashes between rival groups of fans began circulating, and soon everyone was on their guard.

The major flashpoint outside the stadium was an ugly incident indeed, but also something of a misunderstanding. One Liverpool supporter bought a hot dog from a street-vendor, but apparently tried to pay for it in sterling. The vendor was not prepared to accept this, and demanded payment in francs. The Liverpool supporter did not have any local currency though, and so after a heated argument, eventually he just turned and walked away, hot-dog-and-all. The vendor was so angry that he did something that was bound to trigger unhappy memories of a year before – he drew a knife from his stall and slashed the Liverpool supporter with it.

Other red-shirted fans ran up to intervene, and the vendor was soon overpowered. But those who witnessed the confrontation only from a distance appear to have misinterpreted what they saw, and within minutes, the rumour was circulating rapidly around the outskirts of the Heysel Stadium that Juventus supporters had brought knives with them into Brussels, and that one of them had already stabbed a Liverpool fan. It was happening again, it seemed, the Italians were after Liverpool blood once more! Even though the vendor was almost certainly not a Juventus fan at all, suspicion began to give way to anxiety.

As fans of both sides reached the stadium, they shared the disgust the Liverpool club delegation had felt a few days earlier at the sight of a ground that looked like a reject project from a DIY television programme. Many of the Liverpool supporters had arrived without tickets, but this did not prove to be a major difficulty, as almost nobody manning the turnstiles made any attempt to check anybody’s ticket, nor to see whether they were carrying anything inappropriate such as weapons or alcohol. Some fans did not even go to the turnstiles – the cinder-block outer walls were so brittle that it was with very little effort that anyone wanting to get in could quite literally kick holes into them with their feet.

Belgian police at Heysel investigate a hole that has been kicked into the outer wall by ticketless fans. The stadium was so dilapidated that the cinder-block walls had become brittle and easily-breached.

The Liverpool fan contingent in the stadium, as it turned out, was not much smaller than the Juventus one after all, thanks to hundreds of fans getting in without tickets. But the Liverpool supporters were crammed into a smaller space than their Italian rivals, due to Section Z being allocated to ‘neutral’ spectators. On a hot, humid evening, the Liverpool fans found they were getting uncomfortably overcrowded, and this was not helping the general temper. They also found that on the other side of a flimsy chicken-wire fence, large numbers of Italian fans were starting to gather. The inaccurate rumours about a Juventus fan knifing a Liverpool fan outside the stadium were still circulating.

The exact flashpoint inside the stadium is still disputed to this day. As is so often the case with football fans, there is an undignified tone of “They-started-it-No-they-started-it!!!” from both sets of supporters, but what we do know is that there was a lot of missile-throwing back and forth over the fence for some minutes. It was not difficult for hooligans on either side to find missiles to throw – they simply had to crouch down and pick up a piece of the invariably-loose concrete from the ground, and then hurl it. What actually triggered this ‘concrete-badminton-match’ is not certain. It might just have been paranoia at standing so close to rivals, but one anecdote that a number of different Liverpool supporters agree on – and appear to have arrived at independently of each other – gives us the only known possible starting point for the riot.

One Liverpool supporter, who appeared to be only about fourteen years old, had somehow ended up standing in Section Z, surrounded by Italian fans. Liverpool supporters stood on the other side of the fence claimed that they saw the Italians beating the boy up, and that the Belgian police were just ignoring it – somewhat reminiscent of the Italian police a year earlier. The Liverpool fans further claimed that they started throwing missiles as it was the only way they could come to the boy’s aid with the fence in the way. When that failed – only provoking other Italians who had been minding their own business into throwing stones back – the Liverpool supporters started charging the fence in order to knock it down, and to intervene more directly.

(The story about the boy being attacked by Italians is on balance likely to be true, but it is not definitive, as nobody has ever been able to establish what happened to him. There was no dead body – he clearly was not one of the thirty-nine people who died running away from the riot – there is no obvious word of him on any of the hospital reports from that night, and he has never come forward in the twenty-eight years since to set the record straight. Therefore, while no alternative explanation has ever been offered for how the fighting began, this story should still be treated with a measure of caution.)

Stadium plan of Heysel, annotated to demonstrate which fans were where, and the movements at the start of the riot. (Please click on the image for a clearer view.)

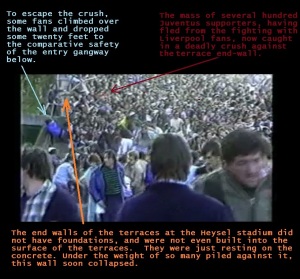

Most of the Italians in Section Z only became aware that something serious was happening when the fence came down. They saw a small pocket of Liverpool supporters right where the fence had been standing suddenly charging forward in a group. They were repelled by the Juventus fans nearest to them, but after a moment charged again. Once more they were repelled, but with noticeably more difficulty. The Italian fans nearest the fallen fence were by now becoming increasingly frightened, while down by the pitchside, the Belgian police still seemed reluctant to step in and keep the peace. Then the Liverpool supporters charged again, and this time, the Juventus fans panicked. They broke up, turned and ran, heading along the width of Section Z towards the extreme end of the terrace, which was lined by a concrete wall. Many other fans were stood in their path, and startled by the sight of a fierce stampede of opposing fans heading their way, turned and ran as well. The more fans broke into a run, the more likelihood there was of confusion and of fans colliding with each other, and the less room there would be as they neared the end of the terrace. The decayed concrete broke up beneath the feet of many of the retreating Italians. This caused some of them to stumble and fall, to be inadvertently trampled on by fellow supporters immediately behind them. But the majority reached the wall at the far end, and soon there was a mad scramble of hundreds of people trying to climb over the wall or over the perimeter fences right at the front. People who had been standing immediately next to the wall were quickly swamped by a raging torrent of panicking supporters. Many were soon being crushed against the wall, while others were being crushed against each other, or trodden on by those trying to climb.

The deathly crush of spectators at the Heysel Stadium in Brussels. 39 died of asphyxiation and other crush injuries.

It was a sign of how awful a condition the stadium was in that the walls at the ends of the terraces did not have foundations, and indeed had not even been built into the surface of the terrace. Instead, they had been erected in place on the concrete over fifty years earlier and simply sealed into position (kind of) with a thick smear of cement. By the mid-1980’s of course, that cement had long-since decayed, and all that was holding the walls up was their own weight. Under the even greater weight of hundreds of panicked people pushing against it, such an unstable structure could not hold up for long. Sure enough, the wall at the end of the terrace gradually began to teeter over, and then collapsed altogether with a wince-inducing cracking noise that echoed all around the stadium. (This is where the idea of Liverpool fans ‘pushing over a wall’ comes from, but in truth, they could not have done so, as they were near the opposite end of the terrace.) The teeming multitude of bodies that had been pressed to the wall toppled over as well, en masse. Under the chaotic pile-up of hundreds of squirming bodies, there was no room even for air to get in.

It is often assumed by some people that the collapse of the wall itself caused the deaths, possibly by falling on people, but there is a school of thought that suggests that the crush-pressure might well have been relieved by it instead, that the deaths were already certain by this point, and that the death-toll may even have been reduced by it. This is possibly true, but as large numbers of people collapsed into a pile-up, it seems likelier to me that the sideways pressure was simply replaced by the downward pressure of gravity and body-weight.

Whatever the case, thirty-nine people died of crush asphyxia while the TV cameras of the world were pointed at them. Hundreds more were injured.

The riot would carry on for several hours afterwards, mainly with Juventus fans at the other end of the ground flying into an understandable rage when news reached them of the deaths in Section Z. With the fighting at last calming down around two hours after the wall collapsed, the Final itself actually went ahead – UEFA had concluded that playing the game would be the only sure way of keeping the crowd occupied long enough to bring in reinforcements to help the police evacuate the stadium in some semblance of good order. For what it was worth, which was very, very little, Juventus won the game 1-0.

The Liverpool supporters had certainly never meant for anybody to die, and indeed some never even found out for some hours afterwards that anybody had died. So any cries of “Murderers!” are simply ignorant – either ignorant of what really happened at Heysel, or ignorant of the correct definition of murder i.e. a premeditated act deliberately and wilfully calculated to take a life. Nobody died in the fighting itself. And the blame for the riot cannot be laid exclusively at the door of the Liverpool supporters either. For instance, it is perfectly fair to argue that there was considerable vile behaviour by Juventus fans as well throughout the course of that evening, both before and after the crush. The appalling condition of the stadium played a huge role in the riot too, especially its crumbling terraces providing copious ammunition for missile-throwing, while the shambolic organisation of the event, especially the failure to control entry to the ground, and the spineless policing were major factors too. AS Roma fans have to take a slice of indirect responsibility as well, for their unprovoked knife-attacks on the Liverpool supporters the previous year. Now, to assume fans of Roma and Juventus are all just the same simply because they are both Italian clubs is like saying fans of Manchester United and Chelsea are all just the same simply because they are both English clubs. (It is to see fellowship between two sets of fans who, in reality, can hardly bear the sight of each other.) But even so, any layman from another country not au fait with the different rivalries within Italy is always going to have trouble seeing the difference, and the attacks were bound to leave a legacy in the victims of bitterness and paranoia towards Italian fans. Margaret Thatcher’s Government should also reflect on their own failure to respond to the fighting in Rome, as it left many Liverpool supporters convinced that they would have to take the law into their own hands in future. (It is therefore bitterly ironic how rabidly Thatcher reacted to Heysel, where the boot was on the other foot, as it were. Her attempt to explain away the Disaster took the form of making out that Liverpool was an unusually violent city, which seems an utterly perplexing notion, given the far higher rate of hooligan incidents among football fans in other English cities, especially London.) Above all, UEFA was greatly culpable too, for the insane decision to use so decrepit a stadium for such a prestigious event in the first place, and for the mindless ticketing arrangements that allowed rival fans to stand within yards of each other.

But even so, the Disaster itself i.e. the human crush that took thirty-nine lives had been triggered by a pocket of Liverpool supporters stampeding across the terrace to attack their rivals, and in terms of narrowly trying to establish the Disaster’s immediate, direct cause, the culpability does ultimately lie there. The reasons the Liverpool supporters did it are plausible, understandable, even forgivable eventually, even if they are not actually excusable or justified.

But they were not murderers, and those who try using that term to describe the rioters at Heysel usually do so for cynical reasons. Using a tragedy that cost nearly forty lives as ammunition for attacking a rival club, for instance. Those who do so might claim that they only wish to see justice for those who died, but it is usually very obvious when that is not the case, and it is also quite contemptible that anyone would take advantage of such horrors for the purposes of anything so petty.

4th Myth – Hillsborough. “It was the Liverpool fans’ own fault that there was a crush! I mean, look at the Nottingham Forest fans, they didn’t arrive late, they weren’t drunk, there was no crush at the Kop end of the ground! All the trouble was on Leppings Lane!”

NOTE: In the original release of this essay, I rather copped out and didn’t bother including a myth from the Hillsborough Disaster of April 1989, as I’d already spent months writing up dozens of essays debunking many such myths – I just directed readers to the links to the Hillsborough Disaster Archive index at the top of this page. However I have since come to realise that there is at least one myth relating to Hillsborough that I have never fully addressed.

There are so many myths relating to the Hillsborough Disaster that it can be a rather gruesome ‘lucky dip’ trying to select which one to tear to shreds. Even if Hillsborough’s mythology isn’t as wild as Heysel’s, there is in fact even more of it, and some of it has been even more heavily-ingrained in the public consciousness.

Most of the myths relating to Hillsborough I have done a very detailed job of debunking elsewhere (if I may say so myself), but there is still one that I feel could do with addressing. At the time of the Disaster, Nottingham Forest Football Club, the ‘other’ team at the stadium that day, was managed by Brian Clough, one of the most famous coaches/managers in recent British football history. Always outspoken, frequently insensitive, a little over a year after he retired, Clough wrote his autobiography. In the book, he attacked the Liverpool supporters who had been at Hillsborough, stating that “Liverpool fans who died were killed by Liverpool people”. He invoked the oft-told story of large numbers of Liverpool supporters arriving at the ground late, having supposedly sat drinking heavily in the nearby pubs until just minutes before kick-off, and then created such disorderly pressure on the turnstiles that the police were forced to open an exit gate to allow them in, leading to a bigger crush on the terraces. When interviewed about the book for ITV by Brian Moore, Clough defended the views he had expressed about the Disaster by comparing the behaviour of Liverpool supporters unfavourably to the behaviour of the Nottingham Forest fans at the other end of the stadium. Clough pointed out that, supposedly, all the Forest fans had taken their places in the South Stand and Spion Kop terrace in good time, and that there were no troubles or difficulties of any description among them. The Liverpool fans, he insisted, had brought trouble on themselves by drinking too much and being late. This urban myth is still given voice with wearisome frequency by many people, both football fans and the wider public, even today.

What actually happened; –

Well firstly, as I have made very clear with considerable supporting evidence in numerous other essays – see a list in the links at the bottom of this page – the Hillsborough Disaster was not the result of lateness or drunkenness at all, but of a series of crowd-handling blunders by the South Yorkshire Police, which led to large numbers of spectators being directed into two fenced enclosures that were already full. The behaviour of Liverpool supporters was not perfect, but it was nothing remarkably bad either, and played no role in causing the Disaster.

But just for once, let’s not focus on the Liverpool supporters. Instead, let us have a closer look at the other side of this comparison that is often drawn with their counterparts. Was the behaviour of the Nottingham Forest supporters really so much better and more orderly?

To answer this, I would like to quote the words of then-WPC Debra Martin, who in 1989 was a Special Constable in the South Yorkshire Police, and was on duty at Hillsborough on the day of the Disaster. She is probably most famous for being one of the key witnesses whose testimonies establish that Kevin Williams was still alive as late as 4pm, undermining the outcome of the Coroner’s Inquests. But in fact, at a key stage in the day she was one of the officers deployed to the east end of the stadium, off Penistone Road, which had been allocated to the Nottingham Forest fans. What she experienced while she was there indicates that there was at least as much disorder among the Forest supporters as there was on Leppings Lane. In a conversation with Hillsborough campaigners Anne Williams and Sheila Coleman, recorded in 1992, Miss Martin revealed the following; –

“…They told me to go to the Forest side to help bring in the VIPs. It was about lunchtime and I was keeping an eye out for ticket touts who [sic] we had been told to arrest on the spot. After the VIPs had gone in I was told to go into the ground myself. By this time the kick-off wasn’t too far off. At the Forest end they had closed most of the turnstiles but one was still open. There were police everywhere and some of the fans were throwing their fists and being abusive. And then, suddenly, one of the side gates opened so the fans just ran through this side gate not bothering with the turnstiles. All these bodies went rushing by and I just got caught up in the main stream. There was a bobby there on horseback and he leant out of his saddle and grabbed hold of my anorak collar… I remember being on my hands and knees and climbing up a man’s back and then, nothing. It was like someone had thrown a blanket over my head. It all went black and I don’t know for how long. When I woke up I ‘d got my hands over my head and I was sat in the corner of a wall. By this time they had got the gates closed. This man was standing on the other side and I could see he was really frightened. I wanted to get out but he said, ‘I’m not letting anyone out.’ I told him, ‘You’ve got to let me out,’ so he opened the gate just a crack and I wriggled through, protected by that same bobby on horseback who was right behind the gate. He said to me, ‘Thank God you’re all right. I thought I’d lost you.'” (Source: When You Walk Through The Storm by Anne Williams with Sean Smith – Chapter 6 Debra’s Story, pages 81-82.)

Now I am certainly not trying to imply that the Forest fan behaviour was egregiously bad at Hillsborough either – by the standards of the 1980’s, even the above was nothing desperately unusual. But there is nothing to suggest that the average of Forest fan behaviour on the day was any better than the average of Liverpool fan behaviour, and it is entirely arguable that it was worse. The reality is that the only reason Liverpool supporters were later getting into the ground than their Nottingham Forest counterparts was the ridiculous imbalance in the allocation of entry points, and nothing to do with fan behaviour; there were eighty-three turnstiles at Hillsborough, and sixty of them were allocated to the Nottingham Forest fans.

A map of Hillsborough, annotated with details about crowd distribution. These explain the *real* reason why the Liverpool supporters took far longer to get into the stadium than the Nottingham Forest fans.

While it is true that Forest had a larger ticket allocation, it was nowhere near as much as three-quarters of the tickets, and yet they were given nearly three-quarters of the turnstiles. Worse, only seven of the turnstiles on Leppings Lane fed the terrace at that end, meaning over ten thousand of the Liverpool supporters had to enter through just seven turnstiles. Further, all the Liverpool supporters had to enter through one very cramped concourse only about thirty metres across on the corner of Leppings Lane, whereas turnstiles allocated to the Forest fans were spread out all around the South Stand and the Kop end of the ground. And – yes there’s even more – as the Leppings Lane end was the ‘Away team’ end of the stadium, it tended to be the part of the ground that was given lowest priority during routine maintenance, and some of the turnstiles the Liverpool fans were trying to enter through were dilapidated and kept breaking down while in use.

Quite simply, it was far, far easier for the Nottingham Forest supporters to get into the stadium than it was for the Liverpool supporters, irrespective of how either crowd was behaving. Raising fan behaviour on the subject of Hillsborough is a red herring.

Conclusion:-

The question we started with was “Why are stadium disasters always prone to urban mythology?” As I intimated while discussing Heysel, some of the false versions are maintained simply because they are appealing to fans of rival clubs whose interests are exclusively vicious one-upmanship. Celtic supporters, for instance, are unlikely to offer many objections when they hear the timeless crock about Rangers fans changing direction on Stairway 13. While Manchester United and Everton fans to this day still routinely taunt their Liverpool counterparts with tacky, ill-informed chants of “Murderers!” which are sometimes even used in reference to Hillsborough as well as Heysel.

In the case of Hillsborough itself though, the myths are not just convenient for puerile chanting. They became heavily-embedded in the public consciousness by a premeditated and cynical blame-shift operation by the South Yorkshire Police force, when it faced considerable public anger for its appalling mishandling of the crowd.

But none of this really applies to Bradford City. Rival clubs do not tend to use the Valley Parade Fire as ammunition for vindictive songs of unabashed cruelty, and while there was a very brief attempt in the media to try and make out that the Fire might have been arson by supporters throwing flares, it was soon dismissed and never took the slightest hold on the public. The West Yorkshire Police were, correctly, never blamed for the Fire, indeed their officers were rightly commended for performing great heroics to help fans evacuate the stand. There was no orchestrated campaign by the police to shift blame onto the Bradford supporters, as there was no blame for them to shift from themselves in the first place. And yet there remains the odd myth about locked doors that never quite goes away.

I suspect the most frequent reason these myths start is just human impatience. There is a sad and needless tendency to rush to judgement. There is no doubt, for instance, that many, many people had prejudged the causes of the Hillsborough Disaster, probably within moments of hearing about it, and certainly long before the Taylor Report was published. In many cases, when the real facts emerge, stubborn pride forbids confessing to being too quick to point the finger. One way to avoid such a confession is simply to argue with what the real facts say.

Another reason is almost the exact opposite emotion, but a similar mindset – gradual loss of interest. A disaster will always draw everybody’s attention at first, but after a while many people simply get bored and stop paying attention. So when corrected information is announced, those who have become bored will simply not be listening, and so the corrected picture of what happened will never register. It can be astounding how long an urban myth can be kept alive just through this lack of general interest.

In the case of all four mythologies though, there is a cruelty, intended or not, at their heart, as the dreadful weight of guilt over the dead and the traumatised is placed upon the wrong shoulders. Even when the accused knows their own innocence, it is difficult not to be swayed at least a little by the accusation. Certainly many survivors of Hillsborough started feeling irrational guilt once the police attempts to smear them were published in the British media. Whoever was responsible for the Fire Exits at Valley Parade might well share an equal sense of irrational guilt – for locking doors that he had not locked at all. Some Liverpool supporters who rioted at Heysel might well feel they really are murderers even though they never wanted anyone to die, and were probably only fighting to protect someone who was being bullied by rival fans. Do some Rangers fans who survived the Ibrox Disaster feel to blame for what happened, as though ‘in spirit’ they really did suddenly turn back and try to plough recklessly through a dense crowd on a steep staircase? If they do, that feeling is cruel and unfair.

These myths only hold credence in the public consciousness precisely because so many people still accept them without ever pausing to check them. But however many people might believe something is not important. What matters is whether or not it is true.

None of these myths is true. Not one.

_____

More myths about stadium disasters can be studied in these essays about Hillsborough; –

Ticketlessness Was Not A Factor, And This Is How We Know

More On Thatcher – That Quote That Never Goes Away

Hillsborough In Its Correct Historical Context

Pushing & Shoving? What Pushing & Shoving?

Lateness Caused The Disaster? Are You Serious? What Lateness There Was Saved Lives

Oh, It’s The Drunken Fans Chestnut Again, Is It? Don’t Even Go There

Forged Tickets? Only If You Think Star Wars Is A Documentary

February 23, 2014 at 11:52 pm

A very interesting read! A lot of the work I have done looking at crowd behaviour in mass emergencies involves debunking the myths that often emerge in the aftermath of disasters. These myths tend to revolve around blaming the crowd in some way for any casualties that happen and I would argue that this can deflect blame away from chronic crowd mismanagement- which usually emerges as the real cause of the disaster once a detailed examination of events has been done. See my blog for more details of how I try to take apart these myths about the crowd

http://dontpaniccorrectingmythsaboutthecrowd.blogspot.co.uk/

February 28, 2014 at 1:59 pm

Thank you, Chris. Yes I did study some of the posts on your blog a few weeks ago. Refreshing to read the work of someone who grasps how crowds really function, including the full implications of how a crowd is not able to think with one mind.

This other essay from last year discusses the involuntary nature of crowd movements within a confined space as well; –

March 4, 2014 at 12:14 am

Egress from certain stadium was always something of a lottery for many years – it’s a pity some clubs never learn.

Note in this photograph, the cars in the background – it was taken only 3 years ago – this is one of two exit stairwells from a stand with wooden benches which is currently restricted to less than 4,000 fans.

‘Enjoy’

May 29, 2014 at 11:27 am

Interesting read, really well researched, and I’d forgotten much of this. I wonder whether the attitude of S Yorks Police at Hillsborough had been shaped, not only by their “understanding” of Heysel, but also by events such as the Battle of Orgreave (where the Police had assaulted a group of picketing miners some years previously, and been praised by the government for doing so).

Certainly, the Thatcher view of the “enemy within” was prevalent in many of the police’s dealings with football fans in the 1980’s (and some fans did everything to encourage that attitude).

July 17, 2015 at 10:03 pm

Excellent piece – thanks for sharing. With regard to the disaster at Ibrox, the myth which you described in some detail was STILL being banded about 30 years after the accident. I personally feel that Rangers FC were very heavily culpable – and yet due partly to the myth, and partly to the absence in 1971 of the blame culture that would plague British society decades later, the club were largely let off the hook.

July 18, 2015 at 4:29 am

The mythical version of the Ibrox Disaster is, alas, still being propagated, probably inadvertently, in the media even today.

In some ways, it doesn’t really matter that much that Rangers were not indicted as heavily as they might have been within the Law, as once Willie Waddell took over the club, he effectively indicted it himself, and made damn sure that there could be no repeat. Voluntarily accepting full responsibility and going to the enormous lengths the club did to make Ibrox safe(r) is at least as good as having a court force that responsibility onto it.

I should mention that I’m not fond of the term ‘blame culture’. It’s usually meant as a pejorative and implies legalist whinging. While there is some truth in the idea that it happens, it is often used to undermine legitimate grievances, and to stave off investigation and finding of serious failures that should be exposed. (Hence the foolish and cynical tendency to growl at Hillsborough campaigners, “Why don’t you people just get over it?”)

November 1, 2017 at 3:48 pm

Is there any evidence online that Heysel stadium was pencilled in for demolition before the disaster in 1985? I’ve looked and can’t find any so far.

November 4, 2017 at 6:42 pm

Sorry for the delayed response. I’ve been moving home and haven’t had much internet access.

I don’t have an internet source for that specific piece of information (although I imagine it’s going to be on a site or two somewhere), I got it from several books. One of them was From Where I Was Standing by Chris Rowland and Paul Tompkins.

http://www.lfchistory.net/Articles/Article/2832